Evidence-Based Approaches to Public Health: Epidemiology – Causality: Association vs. Causation

In this tutorial, we will explore the critical distinction between association and causation in epidemiology. While association refers to a statistical relationship between two variables, causation means that one variable directly influences another. Understanding this difference is crucial for public health professionals, as it affects how research findings are interpreted and how public health policies are shaped. This topic is also essential for the Certified in Public Health (CPH) exam.

By the end of this tutorial, you will understand the concepts of association and causation, the challenges in establishing causality, and the importance of this distinction in public health research. Practice questions are provided to reinforce your knowledge.

Table of Contents:

- Introduction to Association and Causation

- What is Association?

- Definition of Association

- Examples of Association

- What is Causation?

- Definition of Causation

- Challenges in Establishing Causation

- Methods to Assess Causality

- Practice Questions

- Conclusion

1. Introduction to Association and Causation

In epidemiology, researchers often observe a relationship between two variables, such as an exposure (e.g., smoking) and an outcome (e.g., lung cancer). However, the presence of an association between these variables does not necessarily mean that one causes the other. Causation implies that changes in one variable directly result in changes in another. Distinguishing between association and causation is fundamental for making accurate public health recommendations and implementing effective interventions.

2. What is Association?

Association refers to a statistical relationship between two variables. If two variables are associated, it means that changes in one variable are related to changes in another. However, association does not imply that one variable causes the other; it merely indicates that they are linked in some way.

2.1 Definition of Association

An association between two variables exists when the occurrence or level of one variable is related to the occurrence or level of another variable. Associations can be positive (both variables increase or decrease together) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases).

- Positive association: Increased physical activity is associated with lower rates of heart disease.

- Negative association: Higher levels of education are associated with lower rates of smoking.

2.2 Examples of Association

- Example 1: Studies show an association between high sugar intake and an increased risk of obesity. However, this does not prove that sugar intake directly causes obesity, as other factors like genetics or physical activity might also play a role.

- Example 2: A study finds an association between watching television and aggressive behavior in children. This association could be due to other factors, such as parental involvement or socioeconomic status, rather than a direct causal link between television and aggression.

3. What is Causation?

Causation refers to a direct relationship between two variables, where changes in one variable directly result in changes in another. For example, if smoking causes lung cancer, this means that smoking directly increases the risk of developing lung cancer, regardless of other factors.

3.1 Definition of Causation

Causation occurs when there is sufficient evidence to show that changes in an exposure lead directly to changes in the outcome. Establishing causality requires more than just an observed association; it also involves demonstrating that the exposure precedes the outcome and that the relationship is not explained by other factors.

3.2 Challenges in Establishing Causation

While associations are relatively easy to identify in observational studies, establishing causation is much more difficult. The following are some key challenges in determining causality:

- Confounding: Confounding occurs when an outside factor is related to both the exposure and the outcome, distorting the relationship between them. For example, age could confound the relationship between physical activity and heart disease, as older individuals may be less active and at higher risk of heart disease.

- Temporality: For causality to be established, the exposure must occur before the outcome. If researchers cannot clearly establish the temporal sequence of events, it is difficult to determine whether the exposure caused the outcome.

- Bias: Selection bias, information bias, and other forms of bias can distort study results, making it appear that there is a causal relationship when there is not.

- Chance: Sometimes associations occur by chance, particularly in studies with small sample sizes. Random variation can lead to spurious associations that do not reflect a true causal relationship.

4. Methods to Assess Causality

To assess whether an association is likely to be causal, researchers use several methods, including:

- Hill’s Criteria for Causation: These nine criteria (including strength of association, consistency, temporality, and biological plausibility) help evaluate whether an association is likely to be causal.

- Experimental Studies: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provide the strongest evidence for causality, as participants are randomly assigned to exposure groups, allowing researchers to control for confounding factors.

- Longitudinal Studies: Following participants over time in cohort studies allows researchers to establish temporality and reduce the risk of confounding, making it easier to infer causality.

- Statistical Adjustment: Techniques such as multivariable regression can help control for confounding factors, allowing researchers to isolate the effect of the exposure on the outcome.

5. Practice Questions

Test your understanding of the difference between association and causation with these practice questions. Try answering them before checking the solutions.

Question 1:

A study finds that people who drink more coffee tend to have lower rates of depression. Can we conclude that drinking coffee prevents depression?

Answer 1:

Answer, click to reveal

No, this study demonstrates an association between coffee consumption and lower rates of depression, but it does not prove causation. Other factors, such as lifestyle or genetics, may be involved in the relationship.

Question 2:

A clinical trial randomly assigns participants to either receive a vaccine or a placebo. After two years, the vaccinated group has a significantly lower rate of infection compared to the placebo group. Can this study conclude causality?

Answer 2:

Answer, click to reveal

Yes, this randomized controlled trial provides strong evidence for causality, as participants were randomly assigned to exposure groups, reducing the risk of bias and confounding. The vaccine likely caused the reduction in infection rates.

Question 3:

A study finds that people who eat more vegetables have lower rates of heart disease. However, people who eat vegetables also tend to exercise more and have higher incomes. What issue might complicate the interpretation of this association?

Answer 3:

Answer, click to reveal

This is an example of confounding, where factors such as exercise and income may be influencing the relationship between vegetable consumption and heart disease. These factors need to be controlled for to assess whether the association is causal.

6. Conclusion

In epidemiology, it is essential to distinguish between association and causation. While associations are often observed in studies, they do not necessarily imply that one variable causes the other. Establishing causality requires a more rigorous evaluation, including demonstrating that the exposure precedes the outcome, ruling out confounding factors, and providing evidence from experimental or longitudinal studies.

Remember:

- An association between two variables means they are statistically related, but this does not imply that one causes the other.

- Causation requires evidence that the exposure directly leads to the outcome and that the relationship is not due to confounding, bias, or chance.

- Methods such as Hill’s criteria for causation, randomized controlled trials, and longitudinal studies help determine whether an observed association is likely to be causal.

Final Tip for the CPH Exam:

Make sure you understand the distinction between association and causation. One helpful exercise is skimming science news articles, and then reading the underlying studies. Did the author of the article state causation from association? Or were they accurate to the source material? How do you know? This distinction is crucial for interpreting research findings and making sound public health decisions, and will be tested on the Certified in Public Health (CPH) exam.

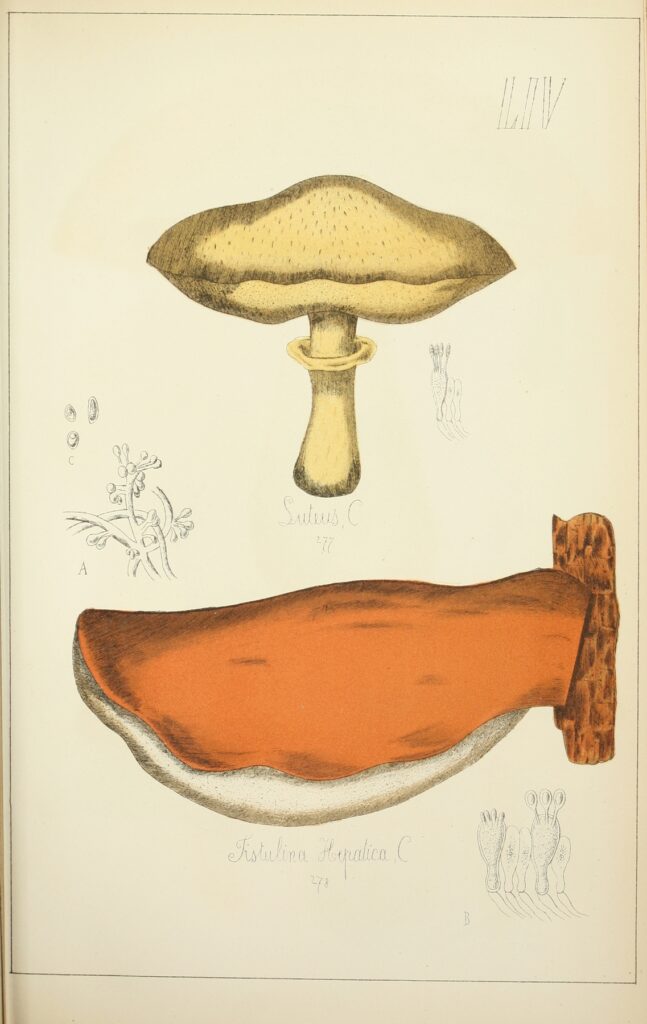

Humanities Moment

The featured image for this CPH Focus is Histoire naturelle des champignons Pl.54 (1883) by Guillaume Sicard (French, 1829-1886). Sicard actually has very little known of himself aside from his work being published within Histoire naturelle des champignons, or “The Natural History of Mushrooms”. This is particularly interesting as the work itself has been seen as a critical work of plant and fungus taxonomical art.