Social Vulnerability and Sickle Cell Disease Mortality: A Call for Equitable Healthcare

Key Takeaways

- Counties with higher social vulnerability had significantly higher sickle cell disease (SCD) mortality rates, revealing critical disparities in health outcomes.

- Social determinants such as unemployment, household instability, and minority status significantly contribute to increased mortality among patients with SCD.

- Black Americans are disproportionately affected, with social vulnerability linked to increased mortality in both urban and rural areas.

- Expanding comprehensive sickle cell care centers and addressing systemic barriers is essential for reducing these health inequities.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is one of the most common inherited blood disorders in the United States, primarily affecting Black Americans. Despite advances in treatment, SCD mortality remains alarmingly high in vulnerable communities. A recent study published in JAMA Network Open analyzed how social determinants of health (SDOH), measured using the Social Vulnerability Index (SVI), impact SCD mortality rates across US counties. The findings underscore the urgent need to address social vulnerability to improve health outcomes for individuals with SCD.

Study Overview: Linking Social Vulnerability and SCD Mortality

The study analyzed SCD mortality data from 2016 to 2020 across US counties, focusing on the impact of social vulnerability as measured by the SVI. This index evaluates factors such as socioeconomic status, household composition, disability, minority status, and housing type to determine a community’s vulnerability to health risks. Counties were divided into quartiles (Q1 to Q4), with Q4 representing the highest level of social vulnerability.

Results showed a stark disparity: counties with higher SVI scores (Q4) experienced a significantly higher age-adjusted mortality rate (AAMR) of 2.65 per 1,000,000 individuals compared to just 0.54 in the lowest SVI quartile (Q1). The rate ratio (RR) indicated that those in the highest vulnerability quartile had nearly five times the risk of mortality from SCD compared to those in the lowest quartile.

Disparities by Demographics

- Gender Differences: Both males and females experienced higher SCD mortality with increased social vulnerability, but females had a slightly higher excess death rate (RR 5.85 compared to RR 4.56 for males). This highlights the compounded effects of social stressors on women, including caregiving responsibilities and barriers to accessing care.

- Age Disparities: The highest SCD mortality rate was observed among individuals aged 25-54 years, with a rate ratio of 4.97 for those living in Q4 counties. Younger patients (<25 years) also exhibited increased mortality in higher SVI areas, suggesting that even younger populations are vulnerable to the impacts of adverse social conditions.

- Racial Disparities: The burden of SCD mortality is heavily skewed toward African Americans, with an AAMR of 11.91 per 1,000,000 individuals, compared to just 0.09 for White individuals. Social vulnerability was strongly associated with increased mortality among African Americans, underscoring the intersection of race and socioeconomic disadvantage.

Social Determinants of Health and Their Impact on SCD Outcomes

The study’s findings reveal that social determinants such as unemployment, housing instability, and minority status are critical contributors to higher SCD mortality. For instance, unemployment has been linked to increased emergency department visits and hospitalizations for SCD, as those without stable employment are less likely to access regular preventive care. Poor household composition—such as single-parent families or those with elderly dependents—also correlated with higher SCD mortality, indicating that family structure and support play a crucial role in patient outcomes.

Geographic and Regional Variations

The geographic analysis showed that most SCD-related deaths occurred in metropolitan regions, particularly in the South, which had the highest mortality rates (AAMR of 2.51 per 1,000,000 individuals). The South also has the highest prevalence of SCD, and access to comprehensive adult SCD care remains limited. These findings highlight the need for region-specific strategies to expand care and improve health outcomes for SCD patients in the South and other vulnerable regions.

Public Health Implications

1. Expanding Access to Comprehensive SCD Care

The findings highlight a critical need for expanding access to specialized sickle cell centers, especially in areas with high social vulnerability. Comprehensive care centers can provide multidisciplinary support, including access to new disease-modifying therapies, preventive screenings, and consistent pain management—all essential components for reducing mortality among SCD patients.

2. Addressing Social Determinants of Health

Improving health outcomes for SCD patients requires a holistic approach that addresses underlying social determinants. This includes policies aimed at improving economic stability, expanding access to affordable healthcare, and providing social support for households in vulnerable communities. Community-based programs that target housing stability and employment can have a direct positive impact on health outcomes.

3. Training Healthcare Providers to Address Implicit Bias

Structural racism and implicit bias within the healthcare system are significant barriers for patients with SCD. Training healthcare providers to recognize and mitigate these biases can improve patient-provider interactions, particularly in pain management, where SCD patients often experience suboptimal care. Ensuring equitable treatment regardless of race or socioeconomic status is fundamental to reducing mortality rates.

Lessons for Health Equity and Future Action

- Focus on Prevention and Early Intervention: Establishing preventive care programs and ensuring early access to treatments such as hydroxyurea and newer drugs like crizanlizumab can reduce complications and hospitalizations for patients with SCD.

- Community Health Workers: Utilizing community health workers to support SCD patients, particularly in high-SVI areas, can help bridge the gap in care by providing outreach, education, and assistance with navigating healthcare services.

- Policy Advocacy: Advocacy for increased federal funding for SCD research and comprehensive care initiatives is crucial. Despite SCD affecting a large number of individuals in the U.S., it has historically received far less funding compared to other genetic disorders like cystic fibrosis.

Conclusion

The study on social vulnerability and SCD mortality provides a stark reminder of the deep-rooted health disparities that persist in the United States. Addressing these disparities requires more than just medical advancements; it demands a comprehensive approach that includes expanding access to specialized care, addressing the social determinants of health, and tackling systemic inequities within the healthcare system.

To truly improve outcomes for patients with SCD, it is crucial to ensure that everyone—regardless of their social or economic status—has access to high-quality, compassionate care. Expanding specialized SCD centers, training healthcare providers to be culturally competent, and increasing federal funding for research are vital steps toward health equity. Only then can we hope to close the mortality gap and provide all patients with the opportunity to live healthier, longer lives.

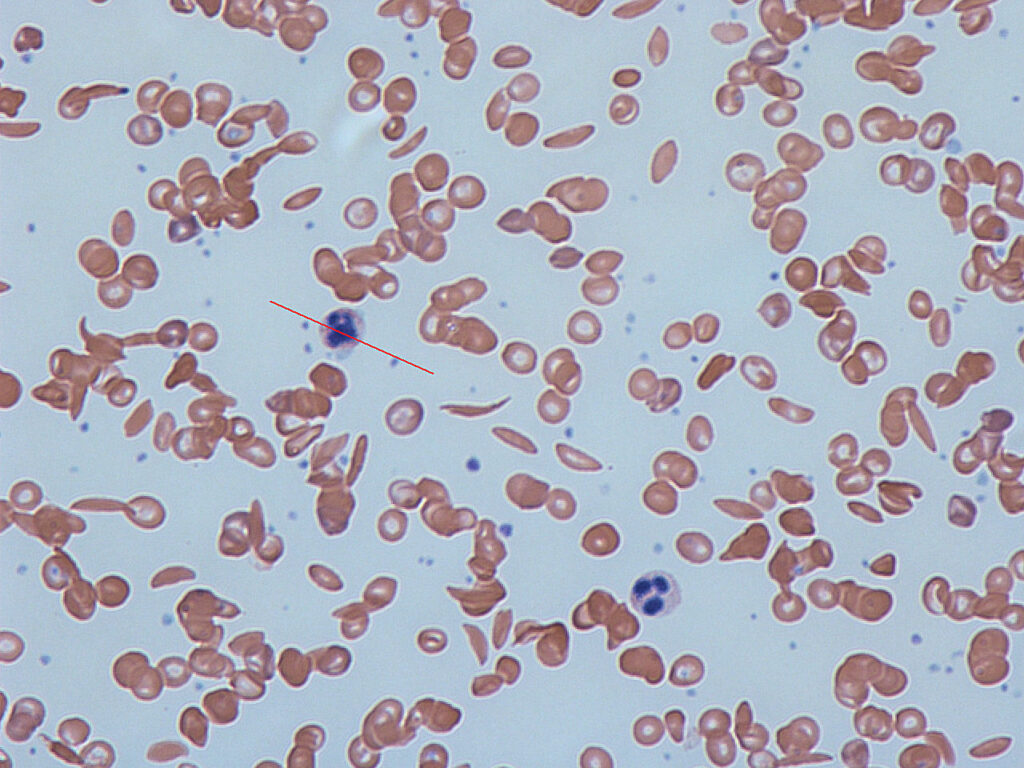

The featured image of this article was sourced from Wikimedia Commons.